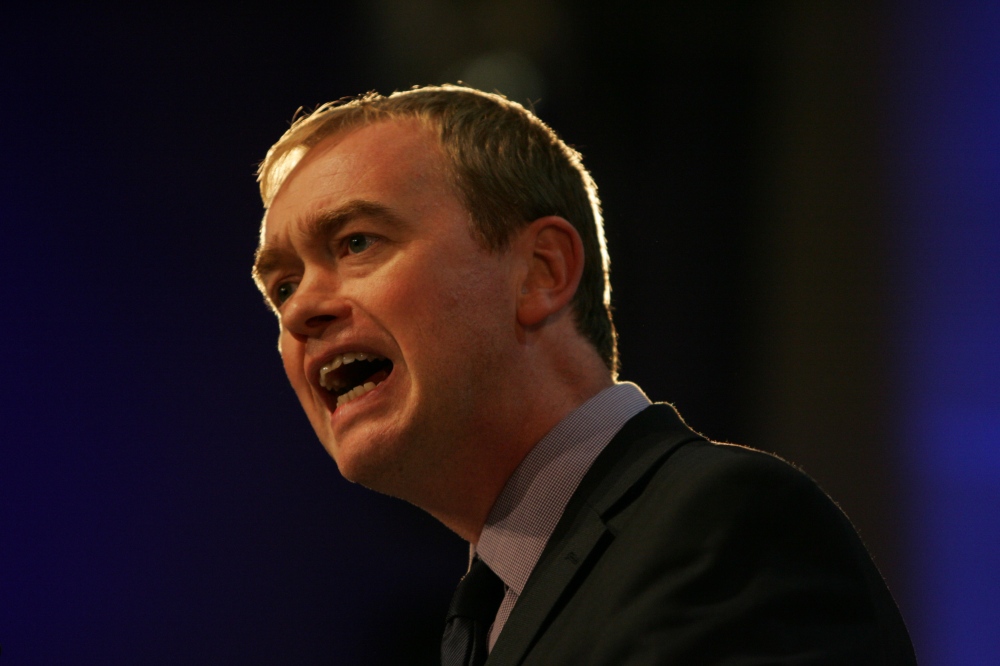

Tim Farron’s resignation statement as Lib Dem leader was one of the clearest, bravest, most moving statements of commitment to Christ by a British public figure in recent years. His conclusion that ‘to be a political leader — especially of a progressive, liberal party in 2017 — and to live as a committed Christian, to hold faithfully to the Bible’s teaching, has felt impossible for me’ has already raised significant questions about British political discourse. This is especially true since Farron’s voting record in these areas is almost indistinguishable from the most aggressively secular MP you could wish to find. Indeed, as Farron explained, ‘there are Christians in politics who take the view that they should impose the tenets of faith on society, but I have not taken that approach because I disagree with it – it’s not liberal and it is counterproductive when it comes to advancing the gospel.’

Though it would be helpful for him to fully retract some of his statements during the election campaign, Tim Farron deserves praise, honour, encouragement and support in putting Christ above political ambition and position. He has served the whole nation in raising the question of how biblical orthodoxy can co-exist with the elite secular liberal consensus that dominates politics. I wonder, though, in his disavowal of any attempt to ‘impose the tenets of faith on society’ whether Mr Farron is promoting the very ideas that made his tenure as Liberal Democrat leader so difficult. The problem is that politics is inescapably about which moral vision is going to be embodied and, at times, enforced by the state. Politics is about making laws, laws which carry penalties if they are broken, and therefore the question is not whether someone’s faith will be imposed on society but whose.

Arguing that Christians shouldn’t ‘impose’ their views on society is simply a tacit way of saying that someone else should. During the debate on same-sex marriage it was rare to hear people argue, ‘I don’t believe in the centuries-old global consensus that marriage should be defined as being between a man and a woman but I wouldn’t want to impose that view on society so I’ll vote against gay marriage.’ Likewise, who can remember someone saying, ‘I don’t believe that the baby in a woman’s womb deserve the status of human life and personhood but I wouldn’t want to impose that view on society so I’ll vote against abortion’? Of course, one might argue that in the examples above the problem is the state prohibiting things, same-sex marriage, abortion, and that the state should allow personal choice even when others might think those choices immoral. But this, too, is a particular moral stance on what role the state should have in society and one open very quickly to a reductio ad aburdsum. Should the state leave the decision to pay tax up to the individual? Should the state leave the decision whether or not to kill or steal up to the individual? Once you concede that the state should use its powers to prohibit anything, it follows that those prohibitions will conform to one vision of society rather than another.

Therefore, when Tim Farron rejects ‘imposing’ his faith on society, and votes accordingly, he is leaving the field wide open to another faith, secular liberalism, to be imposed. No wonder, then, that his treatment in the press was so difficult. For him, and others, to decry the questions about his views on homosexuality and abortion from the media is like complaining vigorously that the other team’s goal was offside when you’ve already agreed to play with your shoelaces tied together. What Mr Farron’s time as Lib Dem leader shows is that, in the end, you cannot sidestep the incompatibility between secular liberalism and biblical Christian values. As the reaction from some political journalists and his own political colleagues has shown, you cannot avoid the fundamental questions of what kind of society that we should have by appealing to some kind of neutral liberalism.

Christians should welcome this revelation. They should welcome it because secular liberalism is one of the most incoherent, ineffective and destructive political philosophies ever to command broad subscription. What, in effect, is the logic of secular liberalism? We live in a world heading towards extinction, our consciousness created by blind physical laws and driven by a ruthless will to reproduce and survive, therefore… What? Love each other? Look after the poor, the lame, the vulnerable? A moment’s consideration shows that these conclusions do not flow from the premise. Secular liberalism is a huge non-sequitur, a philosophy hanging in mid-air like Wile E. Coyote running beyond the cliff edge. The problem with the kind of secular explanations for morality that people like Matthew Parris put forward is that they seek, by evolutionary alchemy, to turn selfishness into altruism. But if altruism is merely a communal metamorphosis of self-interest then what is to stop me cutting out the middle man and pursuing a more individualistic version of that same self-interest? The truth is that values like self-sacrifice, community spirit, philanthropy and much else that our society values fit like a glove with a universe made by a triune God of love but can only wither like a flower left in a vase in the cold, arid universe of secularism. Secular liberalism only maintains its hegemonic status because it rules out these kind of discussions as ‘bringing religion into politics’, an effort to make sure no one mentions the emperor has no clothes.

Christians, therefore, should not resent questions about whether their faith is consistent with their politics, even when it requires them to say awkward, unpopular, things, so long as similar questions are asked of those with secular convictions. Could Ed Miliband, Jeremy Corbyn or Nick Clegg, all atheists, explain neatly how their belief that human life is merely ‘an accidental collocation of atoms’, to use Bertrand Russell’s phrase, fits with the various moral imperatives that drive their politics? Initially, these kinds of questions may seem strange, irrelevant, and obscure but as the implications of running a society on the conviction that there is no authority beyond the human become clearer and clearer, the penny may drop that, over time, society is shaped by its ultimate commitments and these ultimate commitments will shape the kind of laws on the statute book.

I hugely admire Tim Farron for the statement he made yesterday. I wonder whether I would be so brave, I fear I would not. But I wonder whether, though he is ‘liberal to his fingertips’, his resignation indicates the failure of the tactic of Christians attempting to find common cause with secularism in the name of liberalism. Mr Farron’s demise shows that the secular will always win out over the liberal. Rather than appealing that Christian views be ‘tolerated’ in some kind of neutral ‘liberal’ public space, it is time that Christians began to unapologetically argue that society is best served by Christian, rather than secular, values shaping the public sphere. Of course, to do this, Christians will have to connect the political discussion to questions of ultimate reality. What is life about? What are human beings for? What are our real problems? What makes sense of a society that celebrates self-sacrifice and promotes self-obsession? This will take patience, grace, imagination and courage but it is a task not just for those in the political sphere but the whole church. For isn’t the greatest conceit of secularism is that we live in an ‘immanent frame’, locked under an iron sky with no eternal realm beyond, and that this is simply ‘the way things are’? But, if Christian politicians, along with Christian writers and Christian artists, and Christian bankers and Christian plumbers and Christian parents and everyone else besides, can show that, in fact, there is another, more plausible, more compelling, more joyful way to look at the world then we will have made great progress for the cause of the Gospel. If Tim Farron’s resignation is the beginning of these questions re-entering public discourse, then we will have reason to be very grateful for his time as Lib Dem leader.

One Comment Add yours